- Home

- Tim Susman

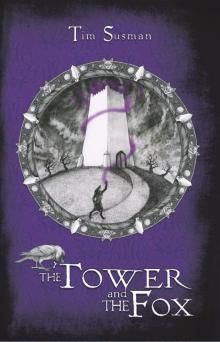

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians Page 2

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians Read online

Page 2

“This is Geoffrey,” Argent said, gesturing to the steaming lizard. “He’s a phosphorus elemental.”

Geoffrey sat up straighter, opened his mouth, and hissed. Kip, who had seen phosphorus elementals, bowed. “Pleasure to make your acquaintance,” he said.

“Can you breathe fire?” Emily asked, staring.

The lizard’s smile grew. “Course I can! Set me down in the biggest fire an’ I’ll breathe happily away. Prefer it to this cold dead air, anyway.”

“No, I mean—can you breathe fire out?”

It tilted its head. “What’choo mean? Out where?”

Master Argent cleared his throat. “If you are admitted to the College,” he said, “you will have ample time to debate philosophy and semantics with our elementals. Geoffrey here is by no means the only one.”

“But I’m the hottest, eh? You said so.”

“Quite right.” The young sorcerer smiled tolerantly and seated himself behind his desk. Kip and Emily set down their bags and came forward; Coppy stared at the lizard a moment. Max remained behind them with Coppy, a bulwark against which Kip could set his back.

Master Argent had brought out two sheets of paper and taken down their names, his words somehow appearing on the paper without any visible pen or motion on his part, when a loud, angry voice called his name at the opening of the tent, and the ruffle of chilly air from the flap opening and closing turned everyone’s head.

A sorcerer with a short white beard, fiery brown eyes, and a mane of white hair that remained thick and full despite the rain strode around to the side of the tent, storming towards the desk from the raven’s side. The raven edged toward Argent on its perch, eyes on the new arrival as he bellowed, “What is the meaning of this?”

Argent remained seated, a small smile meeting the fury of the other. “These are our first applicants to the College.”

The furious master flung his hand out toward the four, and for Kip, the room went silent. The fox tried to turn his ears and then his head through the thick, syrupy air. His breathing was unaffected, but no sound reached him. To his right, Emily appeared to be trying to shout. The silence unnerved him; to his large fox’s ears, the world was an unending bustle of chatter: people talking and walking, birds singing, mice in the walls of buildings. To have all the sound taken away made his fur crawl. He looked back at his father and saw the older fox’s ears flattened against his head, but he remained calm, so Kip tried his best to do the same.

In front of them, the two sorcerers engaged in a heated dialogue, to judge from the expressions on the older one. Master Argent remained placid and smiling throughout. After about thirty seconds, the older man pointed a finger at the younger, gestured toward Kip and Emily, and then turned on his heel and stomped out of the tent.

The air returned to normal around Kip’s ears in time for him to hear the older sorcerer say, “I will be happy to conduct matriculation interviews with legitimate candidates.”

“Excuse me!” Emily said loudly, but the man had already disappeared through the tent flap.

She turned to Master Argent. “Who was that?”

He had been staring past the four of them, toward the outside of the tent, and now turned to her with an attentive smile. “Master Patris, the Head of the College, has some objections to my liberal standards, it seems. But the responsibility for reviewing candidates has been placed in my hands, so—Miss Carswell!”

Argent stood, both hands on the desk, as Emily rose from her chair and whirled. She paid him no mind, but hurried out to the front of the tent, and after a glance at his father, Kip followed.

“Master Patris,” she called as she and Kip emerged into the misty rain. The older sorcerer was halfway back to the Tower, and did not turn as she called his name.

“Perhaps we’d best let him go,” Kip said.

Emily paid him no more mind than she had Argent. “If you allow someone to treat you the way they think they can, they’re going to keep doing it. We have to show him that we will not stand for it.”

“But he’s the Head.” Kip hurried alongside her. He glanced behind, but neither Coppy nor his father had followed. “If you antagonize him, we might not be allowed in at all. Wouldn’t it be better to get in first, and then establish the rules by which you want to be treated?”

“Well,” she said. “You’re a good one with words. Better educated than most men I know our age.”

“Thank you.”

“And don’t you think that education deserves respect?” They had closed the distance between themselves and the retreating sorcerer, near the point in the path where it curved around the corner of the tower. “Master Patris!”

A raven wheeled over them, and the older sorcerer turned, finally. “Candidates are not allowed in the Tower until they have been accepted,” he said, and began to turn again, as though that were the end of the discussion.

“We will not be treated the way you have just treated us.” Emily folded her arms and glared.

He stopped, and straightened. His voice chilled Kip more than the rain. “And how have I treated you?”

“Silencing us without asking. Talking about us behind our backs right in front of us. It’s disrespectful and condescending and we deserve better.”

His eyes narrowed. “Your feet are rather bare to be a bluestocking.”

“I would be proud to be called such. Education and outspokenness are no shame for any person, man or woman.” She did not look over at Kip, but added, “Nor Calatian,” after a second’s pause.

“Education is quite worthy,” Patris said tightly, “and here is a small measure to add to your store. I am the Head of this College, and if I have matters to discuss out of your hearing, then I will remove your hearing. Should you by some fantastical chance meet the requirements to matriculate as a student of this College, you will accept that my authority over you is supreme. If I wish to render you blind, deaf, and dumb—and believe me when I say that the latter is growing more appealing by the minute—then you will trust that I have excellent reason for doing so and you will submit to my authority.”

“And let me assure you,” Emily said, “that if you treated any student the way you have treated us—”

Kip put a paw on her arm. “It was inconsiderate, surely, not to warn us,” he said, and then looked at Master Patris. “But all we ask is the same treatment you would extend to any other student seeking education at your College.”

“When you have proven yourselves worthy of equal treatment,” Patris said with a sneer, “then you may expect to receive it.”

He turned on his heel. Emily shouted after him, “Why do we have to prove ourselves?” but he did not respond, nor turn, and this time she did not pursue him.

Kip felt a sinking feeling in his chest, watching the sorcerer walk away. “Because we always have to prove ourselves,” he said. “Because of how we look.”

“Rubbish,” Emily said. “We’re living in the age of enlightenment, for God’s sake. There’s no reason a woman can’t be a sorcerer. Nor a Calatian, for that matter.”

“I hope not.” Kip rubbed his paws together. “But none has, not ever.”

“Because of people like him.” She didn’t have to specify whom she meant. “Because of people who think men are the only capable creatures God made. Only men can own property or have a voice in government. Can you own property?”

“My father owns a shop,” Kip said. “But he rents the building—well, not the building, but the land. I think he owns the shop itself, but—” He stopped. “It’s all rather complicated.”

“Why should it be? Why can’t he own his shop?”

“We’ve had this argument before.”

She tilted her head. “You and he?”

“Me and Coppy.”

“Oh. The otter.”

Kip nodded. “He came from London, where the Calatians all live in a sort of slum, I believe. And he thinks we are blessed here, where we live alongside the humans and can own business

es and live more or less undisturbed.”

“That ‘more or less’ is worrying,” Emily said grimly. “And you have odd marriage requirements, don’t you?”

“We have to marry in our species.” Kip nodded toward the gates and the town below. “I’m already promised to a fourteen-year-old girl. Alice Cartwright.”

“What does she think of you becoming a sorcerer? You know that no sorcerers are married?”

Kip held up one paw to her, showing the fox’s pads and claws. “Our wedding is three years off, so Alice doesn’t concern herself with my affairs yet. And there are a few married sorcerers. Their wives don’t live near here and they don’t announce their husbands for fear of being made targets, Father says.”

“Fair enough. In my case, I was told one day,” she screwed up her mouth and mimicked a stiff, matronly tone, “‘Put on your nice frock, Emily, you’re to meet your fiancé today.’”

“Your husband let you come apply to the College?”

Then she laughed, and he saw real joy in her face for the first time. “Heavens, no. I managed to get divorced.”

Despite himself, Kip must have shown his shock. “Oh, don’t look like that,” Emily said. “I know two other women who have been divorced.” She laughed again, but more subdued. “We met on alternate Wednesdays. We called ourselves the ‘Old Wives’ Club.’”

It took Kip a moment to reconcile the abstract image in his head of a Divorced Woman—there were none in New Cambridge—with the patient, smiling Emily. “Did your husband take up with other women?”

“Oh, let’s go back out of the rain if we’re to talk about Thomas,” she said. “The subject’s quite dampening enough.”

He turned with her and then stopped, staring at the grey-white limestone wall of the Tower, just fifteen feet from them. “Wait,” he said. If Patris got his way, Kip might never get another chance to be this close to the Tower.

The great building rose some eighty feet in the air, each block the size of his chest. Here at the corner, the stonework was more even and meticulous, alternating long and short blocks rising in a neat right angle, but as the wall extended away from the corner, pits and grooves, the natural peaks and valleys of the stone, made themselves known. From afar, Kip had never seen these, and he felt now as though he were about to shake the hand or paw of a person he’d admired for years, though in fact there was no person save his parents he had admired for as long as he had looked up Founders Hill to the White Tower of the College.

“You want to touch it?” Emily asked.

“I—” He hadn’t even been thinking it, but he did, very much.

“Go.” She pushed him off the path, and his feet landed in damp, soft grass. The blocks of the tower rose closer now. High above him, regular indentations in the wall showed where the windows were, and at the very top—was that a raven? A black shape, indistinct at this distance, stood on the edge.

What was the harm? If he were rejected as an applicant, at least he would have stood this close and touched the stone of the Tower. And that same fascination he’d felt as a small cub, as a teenaged student, as a furtive student of magic with the book his father had taken for him, that fascination rose in him, extending his paw toward the wall.

He took another step and then looked around the grounds. The large admissions tent remained still, the demon at the gate faced away from them, and only Emily watched him. “Go on,” she said. “I won’t tell. I’ll turn away if you want.”

Kip flattened his ears. “I’ve never been this close.”

“It’s a big old building,” Emily said.

“Can’t you feel it?” he asked, and she shook her head. But he could feel it now that he quieted himself and focused. Around and below him, the presence of magic like the pressure of a thunderstorm, registering in the hollows below his ears and in the fur from the back of his paws up his arms, that power that lay in the earth for sorcerers to take as they needed, that power that Kip had tasted a spoonful of, lay here in great quantities. It wouldn’t be the Tower itself, but the presence of so many sorcerers and demons within it, the magical essence brought out of the earth and into the air, that he felt.

His tongue flicked the edge of his lips. He stepped closer, and now the Tower filled his vision, the white veins running through the grey stone, the patterns forming characters of a language he did not yet understand. An insect crawled along one of the stones; a patch of ivy crawled up the side. He followed the tracery of white through the grey, across mortared boundaries to new maps and characters, until Emily said, “Go ahead with it. I’m getting terribly wet.”

Kip leaned forward and delicately pressed three fingertips to the Tower. For a moment he felt only the rough, cold stone. Then his awareness of magic exploded tenfold, a hundredfold.

2

The Tower

Kip had summoned magic from the earth, up in his room in his father’s house, and had grown more adept at it with practice. Still, it required concentration and focus. Here, magic was not deep in the earth but right at his fingers, an immense reservoir of it.

And there was something else, a deep tuneless sound like the distant rumble of thunder that echoed through his bones and then, unexpectedly, resolved into a word, as clear in his head as his own thoughts.

Fox?

Before he could register the word or question its origin, the pressure of the magic surrounding him intensified, sharpened, and then it was surging into him, a giddy rush that quickly set his head spinning. He staggered back, fingers leaving the wall, but the magic remained in him, pulsing below his fur.

* * *

“Your hands,” Emily gasped, and Kip couldn’t spare the concentration to correct her. His paws were covered in an intense purple glow, like radiant gloves, the proof of his trespass made plain for anyone to see.

He turned toward the admission tent in time to see Max, Coppy, and Master Argent come out. Whirling to hide his paws, his ears caught footsteps on the path coming from the Tower. If Master Patris was coming back, if they caught him—

“How do I get rid of the magic?” he pleaded with Emily.

Her eyes were wide. “I don’t know. I barely know how to gather it. I never had anything that strong.”

It burned now, demanding to be used and released. He only knew a small number of spells, and as the desperate seconds ticked by, he could only think of one that he was certain would be safe. He spoke a short series of syllables under his breath and lowered his paws, pads flat down and facing the grass.

The last time he had tried this spell, he’d lifted himself slowly into the air, levitating five feet and then stopping. Now his body shot up alongside the tower, past rows and rows of windows, and he was nearly to the top before he regained control. He rose more slowly after that until he reached the roof, and because he did not dare look below, he looked across at the nearest blocky parapet.

A raven looked back, its feathers sprinkled with rain, eyes gleaming in the brightening morning light.

Kip swallowed. “Brightbeak?”

The raven opened its beak. “How unexpected,” it said in a hoarse croak.

“I didn’t mean to,” Kip said. “It was the Tower. I—”

“We may have much to talk about,” the raven said. “Should you remain, you may find me here. But for now, I think it would be prudent for you to descend.”

Kip gulped. The framework of the spell around him seemed to be draining the magic; at least, he felt no more pressure to use it up. But what if he tried to lower himself and smashed into the ground? “I would very much like to.”

With a clack of its beak, the raven hopped from one crenellation to the next, nearer to him. “I believe Patris will be managing your descent in a moment, if you feel unable.”

“Oh, no.” Kip did look down then, and cupped his ears downward as well. Though the shapes were some eighty feet below, the black-robed figure with the mane of white hair currently pointing up at him was as unmistakable as the fury in the indistinct wor

ds he was shouting. “Not Patris.”

The raven croaked a laugh. “Patris is a bad enemy to have in the College.”

Force seized Kip, none too gently, and dragged him down through the air, fighting his spell. “I know,” he said miserably.

“But,” the raven said as Kip was pulled down below its line of sight, “he was never going to be a friend to you.” It hopped off the roof and soared away and then back to him. “You may end your spell. You’ll be quite safe now.”

And then it was gone. Kip closed his eyes and hesitated—he was still a good ways up—but he could feel the force around him, and he found that he trusted the raven. He loosed the spell.

His descent speeded up, more than he would have liked, but he did not strike the ground so hard that he could not remain on his feet. More threatening to his stability was the red-faced Patris’s shouts the moment he landed, six inches from his muzzle.

“Explain yourself! Unauthorized, unsupervised use of magic is highly dangerous and if you thought to impress us by this ridiculous display, then I am very pleased to tell you that you have achieved exactly the opposite effect. What have you to say for yourself? Well? Is there no explanation?”

Kip opened his mouth to reply after each question, only to have Patris cut him off every time. It was not until Master Argent rested a hand on Kip’s shoulder and drew him back a step that Master Patris stopped to take a breath. “I’m sorry, sir,” Kip said, taking advantage of the pause. “I didn’t mean to! I touched the tower and then there was magic all around. I didn’t know it would do that!”

“Do what? Speak intelligibly, not in your animal noises.”

Behind him, Emily widened her eyes. But Master Argent held up one calm hand and said, “Patris, you know that overeager apprentices have difficulty on occasion with the gathering of magic. Let Penfold explain himself.”

Kip gulped. Patris’s words were too familiar to injure him. “I didn’t mean to gather magic,” he said. “It was just there. And—” Should he tell them about the voice? He was not certain now that he had not simply imagined it. “And I didn’t know how to get rid of it. The only thing I could think to do was send myself into the air. I knew that wouldn’t harm anyone else.”

The War and the Fox

The War and the Fox The Demon and the Fox

The Demon and the Fox The Revolution and the Fox

The Revolution and the Fox The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians