- Home

- Tim Susman

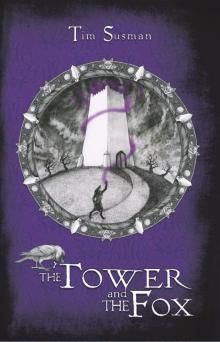

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians Read online

The Tower and the Fox

Book 1 of The Calatians

Tim Susman

Copyright © 2017 by Tim Susman

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Created with Vellum

To Mark and Jack

for making this possible

Contents

Prologue: John Adams Writings

1. The Fox

2. The Tower

3. Victor Adamson

4. Broadsided

5. Testing

6. Admissions

7. Education

8. Physical Sorcery

9. Masters

10. First Spell

11. Fire

12. Woman's Touch

13. Flowers

14. Last Resorts

15. Trial By Fire

16. Bargain

17. Selection

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Also by Tim Susman

Prologue: John Adams Writings

Excerpt from “Letter of Response to the Abolitionist and anti-Abolitionist Movements,” by John Adams, published in the Boston Herald, 1802

* * *

It seems to me that there is another People to which we may turn for guidance on the subject of Abolition of the repugnant practice of Slavery: the Calatians which live among us. In number they are so few that it is possible for a man to pass his life without seeing one, should he avoid the large cities of the British Empire and the towns surrounding the two Colleges of Sorcery in the Colonies, so it behooves those of us who have seen their diligence and example to communicate such to those who have not experienced the pleasure of their company.

Prior to the Council of Birk’s declaration that these animal-people are possessed of souls just as humans are, their lot was not a happy one; in London there was no penalty for the killing of a Calatian until 1623, five years after that Council. Even now in many quarters they are considered lower than man, despite their every efforts to prove themselves equal. And yet no Southern landowner has come forward to attempt to bind them into slavery as they have freely done with the African and West Indian Blacks.

The Calatians, I believe, we regard in some fashion as our children. One of our number, for reasons of his own, created them by magic, and left them to us as our responsibility. The West Indian and African people who have been taken into slavery are more like our brothers, and as any man with both brothers and children may attest, he feels more love for the latter than the former, especially when the brother may have grown apart since their early days. In the same way, we can see that the Crown treats these American colonies, populated by its own children, with greater accommodation than the colonies of the West Indies.

But sons and brothers are still our family, and we owe them the same courtesy and respect. The Calatians have shown how a different race may live among us peacefully, industriously, and to the benefit of all.

1

The Fox

Kip grasped the wrought-iron bars of the school’s gates with his black-furred fingers and pushed his fox’s nose through the gap, staring at the large limestone tower that rose from the center of the well-trimmed lawn a hundred yards away. In bright daylight the White Tower earned its name, but today’s cloud cover darkened the ancient stones and showed the moss and the cracks. It might well be a Roman ruin if not for the still-complete walls and crenellation around the roof. To the left stood a large canvas pavilion, with another barely visible behind it. A stone path cut through the grassy lawn, and beyond those was a small orchard, all of it safe behind the barred gate.

The fox’s eyes dropped to the figure standing two feet behind the gate, an olive-skinned young man with short hair as coal-black as his eyes. “You have to let us in!” he cried.

The young man folded his arms over his tan cotton tunic and looked back at Kip with a half-smile that might have held regret or amusement, or both. “I was told to admit any young men who wished to apply for admission to Prince George’s College of Sorcery,” he said. “And while I am sure it would cause the sorcerers great consternation were I to open the gates to admit a fox-Calatian,” he gestured to Kip, and then dipped his slender hand toward Kip’s companion, “and an otter-Calatian, neither of you is technically a ‘man.’ I am sadly bound by the direct order I was given.”

“We are men,” Kip protested.

“Aye,” Coppy, the otter, said from behind Kip. Where Kip talked with a Massachusetts brogue, Coppy’s accent betrayed his London birthplace. “Should you like, we can pull our trousers down and prove it.”

The young man’s smile did not falter. “There’s no need to expose what’s under the clothes when the proof of your in-humanity swings freely outside of them.”

Kip turned and looked back at his father. His tail, a long russet brush with a white tip, swept from side to side with his agitation. “You said Master Vendis approved me.”

“So he did.” Max Penfold, Kip’s father, stepped up to the gate. Only in the past two years had Kip caught up to his father’s height, but his father stood broader across the shoulders, and where Kip’s large triangular ears were a pure coal black, his father’s were edged with grey. “Please summon Master Vendis, and he will order us admitted.”

“Summon him yourself,” the young man said. “My orders are only to open the gates and show applicants to the Master of Admissions.”

“Just go back into the tower for five minutes.” Kip smacked the heel of his paw against the iron, but not hard. Though he had four fingers and a thumb, his fingers were tipped with claws rather than fingernails, and the heel was covered with a thick leather pad, not fur nor the soft skin of a human hand.

His father placed a paw over his. “He doesn’t need to go inside,” he said. “Look at his feet, Kip.”

The bare feet of the young man hovered two inches above the neatly trimmed damp grass. The young fox’s breath caught. “He’s under a spell?”

“He’s a demon,” Max said.

Kip stared. He breathed in, trying to catch any scent, but the slight breeze blew from him toward the demon. His nose did tickle as if he were smelling peppermint oil, but without the mint, just a cold tingle in the tips of his nostrils.

The young man inclined his head to the older fox. “Then you understand that I am bound by my order.”

“Yes,” Max said. “And you understand that Master Patris will be quite put out by my son’s application.”

The demon smiled, showing preternaturally white teeth. “As enticing as that prospect is, your Master Vendis will also likely be pleased by it, balancing out the annoyance.”

“I would wager that more sorcerers will be put out…” Max exhaled as the young man shook his head. “Let us try another tack. One moment.”

“God’s wounds!” Kip swore, and smacked the gate again. “But Master Vendis promised!”

“Easy to promise, hard to deliver.” Coppy looked up at the taller foxes.

“Calm down.” Max raised a paw, emerging from his brief study, and addressed the young man. “Tell me, were you given any other orders in your duty at the gate?”

“I see no reason to share my orders with you.” But the young man’s smile grew. “Certainly a clever fox such as you can figure them out. Think of the college as a chicken coop you wish to burgle.”

“You foul-mouthed—” Ki

p stopped himself before going any further. He breathed in until the fur on his shoulders and tail settled down.

“That’s not fair,” Coppy said, stepping forward. “Kip here hasn’t been in a coop for years, ain’t that right?”

“It’s not a joke,” Kip muttered, but he drew comfort from his father’s calm. They are only words, he told himself. “What if we wait until another candidate comes up and then come in with them?”

“There’s another on the way,” Coppy observed.

The demon shook his head. “I would be obliged to prevent you.”

Kip turned to look down Founders Hill. Among the gold-tinged maple trees, a figure made its way up the muddy road. In the light rain, he could not make out any details, and the wind brought him no scent. He looked past the figure, down to the Founders Rest Inn at the base of the hill, the black shingled roofs and limestone church steeple of the town of New Cambridge, and the vast expanse of fields and gentle hills beyond. It was as beautiful and peaceful as the cemetery it would feel like if Kip had to return there without entering the College. Maybe he would go to the quarry where he’d practiced lifting rocks with self-taught magic and smash them into each other like stone gladiators.

A horse-drawn cart rumbled by on the street below: the local dairy with their roan gelding. Would the cart mount the hill? Did the College have milk delivered? Did the sorcerers use magic to bring milk directly from the farms? Did they create their own milk by magic? He turned, the need to know burning in him, at his father’s voice.

“Tell me,” Max said. “What precautions have been put in place to protect my son, should he be admitted to the College? We can see behind you the devastation left by the attack—”

“We were here!” Kip pushed his nose through the bars again. Small pieces of brick and wood timber stuck out around the fringes of the large canvas tents, the remains of the grand buildings that had comprised over half the college as of five months ago. “We helped!”

“—and I am most anxious to know that such an event will not be repeated.”

The young man’s smile broadened. He bowed. “I can certainly understand such a concern. Sadly, I am not in a position to answer that question.”

“Please relay my inquiry to a sorcerer who might be able to reassure me,” Max said, with a crisp authority to his voice. “Preferably Master Vendis.”

“I will inquire as to which sorcerer is available.” The demon vanished.

Kip stared at the empty space, then turned to his father. “How did you get him to do that?”

“Demons are bound with very specific orders,” Max said, leaning against the iron of the gates. He reached up to rub his whiskers. “If you can find a way around those orders, you oblige them to seek clarification from their masters. Often they will prefer to do that, as it disturbs the sorcerer, although some demons are much more willing servants.”

“Like the fire elementals.”

“Phosphorus, yes.” Max corrected his son gently. “Although the sorcerers do not speak of the elementals as demons.”

Behind them, Coppy said, “Oh, hallo.”

The two foxes turned. Coming up the path, feet plastered with mud, shoes in one hand and a large bag over the other shoulder, was a young woman with long light brown hair sticking damply to her skin and dress. She showed no surprise at seeing the three Calatians, only laughed and said, “I would wager that those fellows expected a more respectable crowd when they encouraged ‘all those desirous of acquiring an education in the magical arts’ to come to their gates. Is there nobody there yet?”

“They wouldn’t let us in,” Kip said. “And the demon said he was only to admit ‘young men,’ so likely you’ll be no more welcome.”

“Oh, I expected that.” She brushed damp locks away from her eyes. “Their advertisement said specifically ‘any Colonist of magical inclination and ability may apply.’ I memorized it and brought a copy along. I haven’t come all the way from Boston to be turned away.”

“Did you come by yourself?” Max asked.

The young woman drew herself up. She had high cheekbones and flashing grey eyes, and even bedraggled with the rain, she looked dignified. “I did. Mother refused to accompany me, and the sorcerer I learned a little magic from was taken ill.” She glared around at them. “But I made it here safely, and my journey is not over yet.”

“Nor is ours,” Kip said. He extended a paw. “Kip Penfold.”

“Emily Carswell.” She grasped his paw firmly and without hesitation. “Where have you come from?”

He gestured down the hill as Max introduced himself to Emily. “Just the town.”

“Oh.” Her eyes widened. “You live here? Then you were here when it happened?”

“Yes,” Kip began, but was interrupted by movement from behind the gates.

He turned with his father and saw the demon leading back a young man in a long black robe fastened at the neck with a bright silver pin: Not Master Vendis, who was older and had light brown hair. Kip glanced at his father and saw from the upraised ears and smile that the older fox remained hopeful, so Kip smiled as well. This, here, was his first contact with a sorcerer as a candidate for admission, and he would show them he was worthy.

The young man was pleasant enough, his puzzled expression clearing for a smile. “I’m Master Argent,” he said. “Are you…?” He turned to the demon. “Corimea, you told me there were candidates here.”

“So there are.”

“Then why did you not open the gates for them?”

The demon’s voice changed, became older and gruff. “Stand at the gates and open them for any young man who wishes to apply for admission to Prince George’s College of Sorcery, and his family.”

“Young man.” Master Argent shook his head. “You may open the gates for any person wishing to apply for admission. Is that clear?”

“You do not hold the keys to my binding,” the demon said.

Argent kept his smile, but made a small hissing noise of exasperation. “I will have Patris amend your orders later.”

The demon Corimea bowed. “As you wish.”

Master Argent gestured at the gates. They parted outward, pushing the Calatians and Emily to retreat several steps. Kip and Emily picked up their bags and suitcases with alacrity and led Max and Coppy forward, into the grounds.

“Now,” the sorcerer said, “here is an unusual group of applicants.”

“We’re as good as any man who might apply.” Emily stepped to the front.

“We shall see about that, I suppose.” Argent smiled. “All four of you wish to apply?”

“I am Master Vendis’s calyx,” Max said. “This is my son, who wishes to apply, and our friend Coppy, who will not.”

“Highly unusual,” Master Argent said, but he rubbed his hands together as though relishing the prospect. “Come inside and we will discuss whether the College can accommodate you.” He turned and walked along a stone-lined path to the nearest of the two large tents.

“Discuss?” Emily followed at his side as the three Calatians walked behind. “We are here to apply to the College. What needs to be discussed?”

“Come now.” The sorcerer turned so that Kip could see his smile. “A woman intelligent enough to apply to Prince George’s is certainly intelligent enough to know the difficulties involved.”

“Women can learn sorcery if given a chance. There is no reason a woman should be treated differently.” Emily put her shoes down on the stone, wiped her feet on the grass, and stepped into them.

“Nor a Calatian,” Kip added as he lifted his cloth suitcase. He glanced up as a raven flew over their heads, and then another. The first returned to the tower, while the other circled above them.

After the terrible noise and thunder of the attack back in May, the ravens had been the first signal that there were survivors on the hill. Kip had not seen more than one since that night; his father’s sorcerer, Vendis, now sent his raven down when Max was needed, rather than coming in perso

n as he had previously.

When they arrived at the entrance of the tent, Master Argent held the tent flap aside. Before any of them could step through, a black shape flew past, skimming the edges of the cloth. Master Argent ignored it. “The problems are not insurmountable,” he said, “but they must nonetheless be addressed. How fortunate I am to be the first sorcerer presented with a Calatian candidate and a female candidate.”

His smile was fixed enough that Kip could not tell whether he was being sarcastic. Before he could decide, the fox’s attention was caught by a bit of glistening white in the debris around the edge of the canvas. For a moment, he was convinced it was a bone, and the chill of that suspicion followed him into the spacious tent.

Inside, the grey light of morning and the smell of damp remained, but the air that brushed Kip’s whiskers held unexpected warmth. A stately desk stood in the center of the tent, burnished mahogany or cherry—Kip was not very clear on his woods—with loose sheets of rough paper atop it. To the left, a high perch stood that allowed the raven upon it to look down at all of them, and to the right of the desk, a large copper brazier on foot-tall legs and a thick stone base radiated soft light and heat in rippling waves. Inside the open bowl of the brazier, Kip saw a familiar pattern, like blackened pieces of wood bark lying atop a fire, so that bright orange shone through in jagged lines. As they entered, the pattern shifted, and a triangular reptilian head, eyes glowing, opened its mouth to reveal a steaming pink tongue.

“First of the new lot, is it?” it said in a thickly English accent. “Ooh, they’re an unlikely looking bunch.”

The War and the Fox

The War and the Fox The Demon and the Fox

The Demon and the Fox The Revolution and the Fox

The Revolution and the Fox The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians