- Home

- Tim Susman

The Revolution and the Fox Page 5

The Revolution and the Fox Read online

Page 5

“Journeymen,” Moise explained, “do God’s work among the people. For some, it is a calling. For others…” He brushed a hand modestly down his green robe. “It is where we feel most comfortable. But surely you in America have something like this.”

“Er. We used to. Sort of. In New Cambridge, where I grew up, there was a sorcerer’s school nearby, and for a while the healer would come down to the town, and sometimes another sorcerer would come as well. But the sorcerers all worked for the Crown—the King—and the government would tell them where to go. Some work on roads and buildings, big projects that benefit everyone, and some work for the military, and we…” He included Malcolm, who was talking to one of the Chinese sorcerers, “study sorcery and educate new sorcerers.”

“Yes, we know this.” Nephi smiled. “We thought that perhaps having rid yourself of the Crown, you might also have made other changes.”

“We have. We have a representative system of government and we’re striving to make sure that everyone’s interests are balanced. But at the same time, we are a young country and we know that many of the other powers of the world view us as an easy target.”

“Surely not,” Moise said. “Your colleges of sorcery and your military sorcerers are among the finest in the world.”

“Yes, but…” Kip stopped himself before reciting a list of his country’s weaknesses to a foreign sorcerer. “I certainly hope the rest of the world shares your views, but the countries that surround us now have a bloody history of taking from one another.”

“That surround you in America?” Nephi looked puzzled.

“No, no.” Kip made a wide circle with his paw. “Here, in this palace. Holland, England, Spain, France, Prussia.”

The sorcerer’s face cleared, and he laughed. “How correct you are. My own country has had those periods in its history. Now, I fear, we struggle not to be one of the things taken. But surely you live on a new continent far from the Old World?”

“Far in some ways,” Kip said.

“Ah, I take your meaning.” Nephi smiled. “Indeed, we had to send a bird on ahead, and then we could jump to the palace.”

“And now,” Kip said, “you may return whenever you like.”

“With each jump, the world grows smaller.”

They talked a little longer about how the Egyptian sorcerers found new students, and Kip determined that none of the three was a healer. The healers they knew had little interest in exploration and advancement, and none wished to spend the better part of a week in Amsterdam when they had people to attend to.

Kip gathered from this that their healers treated disease as well as physical injuries, which he had thought only a few healers in the British empire could do. He didn’t want to press further; both he and Nephi engaged in the conversation while also holding back important details of their respective colleges and education, and he respected those boundaries. Besides, his main goal was to find a healer, and learning about Egyptian healing practices was helpful but no more so than reading a book about water when you were thirsty.

Two Spanish sorcerers came up as Moise was showing Kip some simple spells he could do with sand. Living near a desert shaped their study of physical magic, and Moise was more skilled with sand than even Alice was. But the Spanish sorcerers barely looked at the sand. “Excuse me,” one said to Kip. “You are…Master Penfold, yes?”

“Yes.” Kip flicked his ears back. Neither the scent nor the features of the dark-skinned men were familiar.

“If it is not a disturbance,” the Spanish sorcerer said, “may we trouble you for the story of the Road?”

From Moise’s expression—unsurprised, polite—Kip understood that Moise had known who he was and had been politely refraining from asking him. “I’m sure you’ve already heard it,” he said. “I can’t tell you—”

“Of course we would not ask how you did it.” The man smiled. “But what was it like, when it disappeared?”

So Kip told the story of the Road between Bristol and New York, how beautiful it had been, how strange it felt to walk along the surface of the ocean with no land in sight anywhere. He talked about how salt had encrusted the surface but you could still see the shimmer of magic, how the waves splashed your feet, how fish swam into view and birds wheeled overhead. He told them how when it disappeared, magic vanished from the world for a moment as though in protest. He left out that the Road had been destroyed by his former mentor Cott, who had perished in the incident, and that Ash, who sat on his shoulder, had been Cott’s raven, her binding undone by the destruction of the Great Feat and reformed in the surge of magic returning in its wake.

Ash fidgeted as he told the story. Their bond was strong, and he did not feel anything like fear from her, but all the same he couldn’t help thinking that the story upset her a little whenever he told it.

“It is quite incredible,” the sorcerer said. “Nobody else alive today has even witnessed the destruction of a Great Feat.”

“I suppose not,” Kip said, although several of the sailors on Cott’s boat were still alive, as far as he knew. “If you’ll excuse me, I must go find my friend.”

Malcolm had moved to the far end of the room, talking with one Chinese sorcerer. As Kip approached, Corvi turned on Malcolm’s shoulder. Without turning himself, Malcolm said, “Ah, here’s my distinguished colleague, Master Kip Penfold. Kip, this is…just a moment, I’m certain I won’t get it right, and I do apologize for that…Master Li?”

“Li is my family name.” The sorcerer bowed to Kip.

Unsure how to respond, Kip bowed back, trying to approximate the motion the other sorcerer had made. It seemed to suffice. “It’s a pleasure to meet you,” he said.

“Please excuse my imposition,” the sorcerer said, “but is it true that you have witnessed the destruction of a Beautiful Miracle?” When Kip frowned, Master Li said, “I apologize. A wondrous magic, one that remains in the world. I do not know the words in English.”

Kip’s ears went back. “Ah,” Malcolm said, “it’s true as true can be, and I dearly wish we had time to tell the tale, for it’s a grand and stirring one. But Master Penfold and I have agreed to travel through the entire Exposition in a single day, and so sadly we haven’t the time to stand and tell the tale again. Should we happen by here tomorrow or the day after, then of course Master Penfold will be delighted to tell his tale, I’m certain.”

“I shall eagerly await your return.” Master Li bowed again, and again Kip tried to return the bow.

“They have no healers,” Malcolm murmured as they left the room.

“Neither did the Egyptians.” They passed through a short hallway and then emerged into a larger room, this one housing three countries’ delegations. The entire left hand wall had been hung with the flag of India, colorful tapestries showing white-robed Indian men riding elephants, standing among peacocks, and casting spells, often in the presence of tall, blue-skinned men who sometimes had multiple arms.

To the right, two flags Kip didn’t recognize shared the wall: one red over white, the other plain white with a gold lion in the center and a sun rising over the lion’s back. “I’ll take those, shall I?” Malcolm asked, walking to the right and leaving Kip to join the crowd of people talking to the nearly dozen Indian sorcerers.

One of them was casting a spell on a bowl in front of him which appeared to be filled with sugar. The brownish-white granules darkened and flowed together, and a rich sweet smell filled the air. “There you are.” The sorcerer raised his head and smiled, speaking with just a trace of an accent. “It is a traditional Indian candy, much like your toffee, I think? But the spices are different. Please. Please.” He broke the mass into pieces and held the bowl out to the crowd.

Kip reached forward to take one along with everyone else. On the far side of the crowd, a sorcerer who hadn’t noticed him before grabbed the edge of the bowl and pulled it away from Kip’s paw. “Sorcerers first,” he said.

The Indian sorcerer looked an apology at Kip

, but only said, “Please sir, do not touch the bowl.”

The other sorcerer let go, grumbling. By this time, several others in the crowd had noticed Kip, and one of them recognized him and elbowed the one who’d pulled the bowl away. “He is a sorcerer, you idiot.”

“What?”

“Don’t you remember the stories of the war?” From their accents and white skin, Kip judged that they were English, but he didn’t know either of them. “That’s Penfold. Er—Master Penfold.” The man executed a clumsy bow.

Two more Indian sorcerers came over and stood by Kip, examining him with great interest. The sorcerer who’d pulled the bowl from him stared. “Penfold? The one who—?”

“Yes, the one who.” His companion pulled him away. “Come on, go make an ass of yourself somewhere else.”

At least they hadn’t asked for the story. If they were from King’s College, they probably knew it well enough already. The remaining sorcerers, however, looked greatly interested, and so Kip, to forestall, asked the Indian sorcerer with the bowl, “I do beg your pardon, but are any of you trained in healing? I have a few questions.”

One of the two who’d come up, a middle-aged man with some grey at the temples, stepped forward. “I am a healer,” he said. “Have you an ailment?”

“Not exactly.” Kip gestured to the side. “May I take a moment of your time?”

“Of course.” The sorcerer inclined his head and walked with Kip to a quieter section of his table.

“Thank you.” Kip let his tail swing free as he left the small crowd. “My name is Kip Penfold and I come from the Lutris School in America.”

“I am Vijay Chakrabarti.” The man smiled. “You may call me Vijay if you have difficulty with the surname.”

“Chakra-barti,” Kip repeated. “Chakrabarti. I will try to remember.”

Chakrabarti inclined his head. “Most kind of you, sir. How may I be of assistance?”

“Do you heal the mind as well as the body?” Kip asked.

“To the best of my ability, although that rests more with experience than with sorcery, you understand.”

“Yes.” Kip smoothed his whiskers back. “The other question is—” He took a breath. “We are looking for a healer to come teach at the Lutris School. Would you, or any of your colleagues, consider that?”

Chakrabarti’s eyes widened. He glanced back to the rest of his colleagues and then leaned in, lowering his voice. “Is this a true offer, sir?”

Kip’s tail swished, but he kept his excitement otherwise under wraps. “It is.”

Chakrabarti considered for a moment. “I must confess to you, sir, that I have not yet attained the rank of master.”

“Oh.” Kip studied the lined face, the grey hairs among the black. “Did you begin your education late in life?”

“Oh, no, sir! Quite the contrary. I began my studies at the age of fourteen. I have spent thirty years as a minister.”

“A minister? A preacher?”

“No, no.” The man smiled, making his mustache flare up at the ends. “I minister to people in the city of Calcutta. Myself and Master Kosaraju and Master Agrawal are from Calcutta. Our colleagues are from the colleges in Delhi and Bombay.”

Kip took in the whole of the Indian exhibit. “How many colleges are there in India?”

“Of sorcery?” Chakrabarti smiled. “Oh, many, many. There are small schools, perhaps thirty or forty, where students may go to learn whether they can perform sorcery. When they graduate from these schools, then they may go to one of the colleges. Delhi, Calcutta, and Bombay are the largest, but there is one in Agra and one in Jaipur and I have heard that one has just been opened in Bangalore.”

“Six colleges.” Kip shook his head. “The British Empire has only one now.”

“Some might consider the Indian colleges part of the British Empire.” Chakrabarti’s smile faded.

“Oh.” Kip didn’t know what to say to that.

“There is more and more interference…” Chakrabarti shook his head and his smile returned. “This is not a complaint I should be making to you. After all, Kip Penfold, you have also felt the heavy hand of the British and you have shaken it off with great success. In fact, I am very pleased to be speaking to you, although it was Master Kosaraju who most wished to see you. It was he who told you about me.”

One of the other Indian sorcerers kept sneaking looks at Kip. That one was probably Master Kosaraju. “I’m glad I was able to attend,” he said.

Chakrabarti leaned in again. “I wonder if you might tell me…”

Here it comes, Kip thought, and prepared to tell the story again.

“How one such as yourself came to study sorcery. It is my understanding that your people are not…sorcerers.”

“Ah.” Kip’s ears stood up. “You don’t have Calatians in India.”

“No, sir, we do not. We know of them, of course, and among sorcerers there is much curiosity. Among the people of India, your people would be regarded perhaps with fear more than curiosity. I am sad to report this.”

“I understand. I am pleased that there is less fear among sorcerers.” Kip smiled, and told Chakrabarti about his father’s relationship with Master Vendis, the procuring of a spellbook, his discovery that he could do sorcery, and his acceptance into the college. “There were many who did not want me to attend, but I worked as hard as I could to prove them wrong.”

“With admirable success.” The other sorcerer inclined his head in a sort of bow. “It must have been very difficult being the only one.”

“I wasn’t.” Kip hesitated. “My best friend Coppy—he was an otter—he joined too, and he died trying to protect the school. Our school—the Lutris School—is named for him.”

“I am sorry to hear it.” Chakrabarti looked like he meant it very sincerely.

“It was several years ago.” Kip cleared his throat. “But tell me about your work as a healer in Calcutta. Do you treat disease as well as physical ailments?”

“I can treat some of the symptoms of disease,” the sorcerer said. He told Kip of his work, how he kept thinking that he should go back to the college to finish his coursework and teach others, but there were always more people who needed his help. “Often I would go to bed exhausted and wake four hours later to a new line of people at my door. But last year, two new healers came from the college, and now I have time to myself. I started taking instruction at the college toward becoming a Master, and I have time to come here and meet new friends from other countries.”

“Are you interested in coming to Peachtree?” Kip asked. “I mean, to America?”

“I would greatly enjoy that.” Chakrabarti turned to his colleagues. “I must consult with the ones in charge of my instruction to gain their blessing.”

“As soon as you can confirm that, it would be very helpful. And if you might be able to secure a recommendation from the master who instructed you, or the head of your college, we will need that.”

“I am sure I can procure that.”

“And I would like you to meet my colleagues…” Kip sent Ash to go find Malcolm and bring him over.

Chakrabarti’s eyes flicked to the raven as she left. “This raven is yours?”

“Yes. She bonded to me—we have a practice of having a companion. Some call them familiars. I can see through her eyes and speak through her mouth.”

“That is exceedingly interesting. I know of familiars; many sorcerers have them. The British attempted to introduce them to our practices, I am told, but we regard it among our people as enslavement of an animal that has a soul as much as we do. The practice has never been undertaken among Hindus.”

“Are all Indian sorcerers Hindus?” Kip asked.

“Not all. Some are Muslim. But we have a long tradition of respecting each others’ beliefs. The College of Calcutta was founded by Shah Jahan in 1639 and although he was Muslim, he specified that the college would always welcome sorcerers of every faith.” He paused and smiled. “You might know Shah Jah

an best as the ruler who commissioned the Taj Mahal.”

“I’ve heard of the Taj Mahal,” Kip said, “but never seen it.”

“Ah! We have a picture here somewhere. I shall find it for you.”

Malcolm arrived at that moment with ravens on both shoulders. Ash hopped from his shoulder to Kip’s as he drew nearer. “Lazybones,” the fox said affectionately. “Didn’t want to fly all the way back?”

In response, she croaked and rubbed her beak against his ear. He smiled and said to Chakrabarti, “I’m not sure it’s enslavement. She takes advantage where she can.”

“Yes, I am sure.” The man didn’t smile, but turned to Malcolm to introduce himself, and Malcolm extended a hand as he said his own name. Chakrabarti only briefly flinched when Malcolm faced him, but did not ask about the Irishman’s eyes, nor did he react in any other way.

“When would you be able to sit down with us for a bit and talk about the college?” Kip asked. “Our college, I mean. Our headmistress is here but is occupied today.”

“I am required to be here this morning into early afternoon,” Chakrabarti replied, “but tomorrow I have a large portion of the day to myself. I would be happy to meet with you then.”

“Fantastic,” Kip said. “I mean it.”

They spent a little longer speaking with Malcolm, Chakrabarti telling him about India and Calcutta, and their debt to the East India Company. “We have fought back armies,” he said, “but what good is sorcery against trade and tariffs and economic power? We may strike down the great Khan’s armies as they ride south to conquer us and yet we have no spell to combat the greed of men when promised riches, no sorcery to tear up unfair contracts signed years ago.”

“My people are similarly afflicted,” Malcolm said, “though we haven’t the might to fight back armies. We had to strike one by one, a little at a time.”

By now the crowds had grown, and one of Chakrabarti’s colleagues signaled to him. “I do beg your pardon,” he said, “but I am needed.”

“Of course,” Kip said. “Thank you so much for speaking to us.”

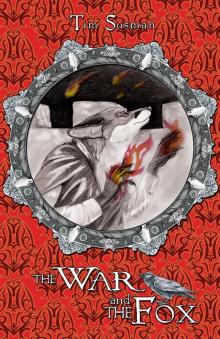

The War and the Fox

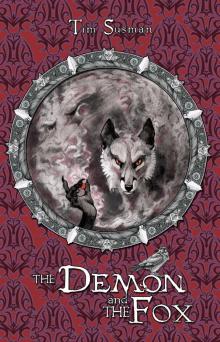

The War and the Fox The Demon and the Fox

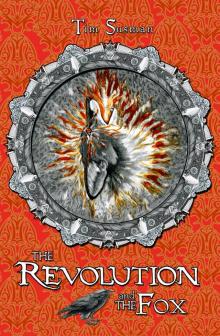

The Demon and the Fox The Revolution and the Fox

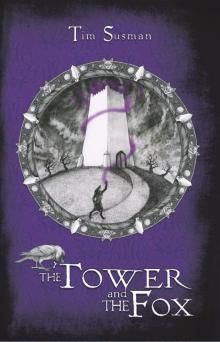

The Revolution and the Fox The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians

The Tower and the Fox: Book 1 of The Calatians